Isn't it curious to think that during centuries, from the end of the antic world to the very beginning of the Roman period, the Acropolis was a totally unknown place to the eyes of the Occident, absent from our images, our dreams, our memories?

During the long period of time before its discovery, or let's say its re-discovery, the Acropolis, obviously, never ceased to exist. On the contrary, the carvings of ancient times, writings of the oldest of explorers show it inhabited, busy and crowded with houses, churches and later on, mosques.

Here, at the heart of this jumble of history, lifestyles and façades, so far away from the place we know, nude, clean and clear, we can see a surge of people, the "acropolitan" people (let's call them that way to settle down the things more easily): composed of Greeks at the beginning, then Turkish, Armenian, Albanian. During centuries, they were the only inhabitants, the only admirers of the Acropolis, which, back then, was simply called the Fort or the Castle.

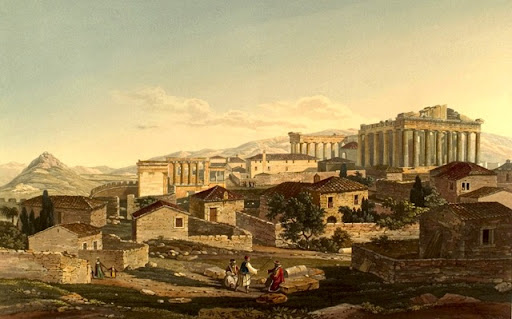

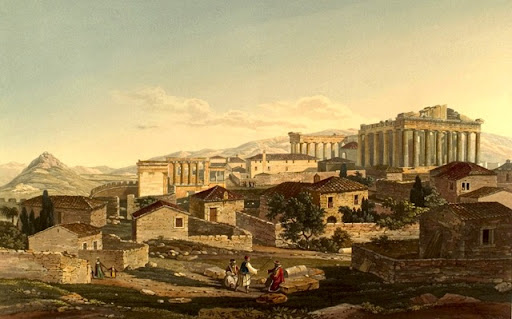

Let's go deeper in this time along with these practically unknown carvings or engravings, showing us this strange and forgotten history. For example, those of J. Stuart & N. Revett (that you can find on the internet), two British travellers who stayed in Greece from 1751 to 1753 and actually saw the old Acropolis in its former and ancient state.

The engravings of these two explorers depict the Acropolis as a place full of houses, streets, olive tree gardens and the flowers taking up the entire place, from the Propylaea to the Parthenon, circling this massive structure with branches.

Inside the temple, the domes of the turkish mosque are shining. Mosque which only was to be demolished in 1842. Further, in another engraving, the Erechteion behind which we distinguish a large house and a courtyard with a couple of cypress.

The old temple seems to be here, a place of meditation: an "acropolitan" seated under his portico looks at the sky with dreamy eyes while, right by his side, people wearing turbans, children and dogs are walking around as if it was a village.

We can feel the same, fifty years later when

Dodwell, another British traveller, author of the book

Views in Greece from Drawings, paints the Acropolis in 1805.

The houses are surrounded with walls, providing tiny courtyards of olive trees and thin cypresses. We can also distinguish a large building, just next to the Parthenon, maybe a warehouse. Shepherds are talking under the bright white light.

No doubts: it's a village. Nothing like a temple, a sacred land or anything else but a village the painter shows us with its hours of fuss and calm. Here, the antic gods are dead and buried. Ultimate traces of their presence: these columns, these faces and torsos on which the acropolitans are talking.

Lots of other travellers, authors, have seen and described this Acropolis, turned into an oriental village, into an makeshift fortress, into a bazaar saturated with marble and statues. From their writings, from their engravings, emanates the same impression both reassuring and sad: the Acropolis did not die to history during these dark centuries but humbly lived, turned into a village, a castle, a bazaar, houses, gardens. The Parthenon, itself, became the Church of the Holy Virgin then a turkish mosque. There was a life upon this rock: an everyday life, at the beginning greek, then turkish, christian, and muslim. What a story for this Holy rock of the ancient Greeks, this Byzantine Castle, this Rock of the Independence.

I'm thinking that, finally, this life above on the rock both secular and religious was maybe in accordance with the antic and former vocation of this place, with the religious Acropolis of Pericles, crowded of people, altars, trophies, cluttered with statues. Life on the Acropolis has gone on its proper way, nourished with the atmosphere of this place where Gods or one God was worshipped.

This is the war that destroyed a part of the Parthenon. Shepherds, inhabitants, merchants had nothing to do with that disaster.

Nowadays, the "acropolitans" are named "tourists". The archaeology became their new faith and the archaeologists the new priest of this secular cult. But after several centuries made of darkness and troubles, I can't stop myself from thinking of the strange destiny this place holds. Because, since it arose - just one century ago - in the occidental conscience, since it became - after 25 years of oversight - the place itself where the reason was born, it is already threatened.

When it was a city, bazaar, fortress, place of meditation, living ashes and refuge of the religions, the Acropolis was going on with its slowly life. Become the high place of the modern cult of tourism, it gives us the see-through message of its centuries, the brightness of its marbles, the purity of the soil, which gained back thanks to the excavations the virginity of its original rock; but it gives us as well the ignorance, the carefreeness, and the excess of the modern crowds.

Between this long silence and this sudden commotion, the time of ancient cults and those of modern culture, it seems like the Acropolis keeps asking us the same question as the Sphinx asked to Oedipus: whether we look at the dawn, at noon or at the nightfall we can still hear a voice murmuring: "Who edified me at the dawn of Occident, praised to the skies at the zenith of the reason, protected me at the nightfall of my gods?" The MAN. And not only the Greek man, but with him, through him, the Oriental man and the Occidental man who, during forgotten centuries, have been able, have known how to live with each others upon this rock which will never be a rock like others.

The monument I've ever preferred on the Acropolis is, on the west part of it, facing the sea and the setting sun, the small temple of Victorious Athena, Athena Nike. There was inside a wooden statue of the goddess, carved from olive tree wood, wingless so she couldn't fly away from the city, represented on her foot, offering in her right hand a fruit: a pomegranate. This statue does not longer exist obviously, no more than she existed at the time of the "acropolitans". But I see in her the clearest, the most durable symbol of the necessary continued existence of the place and this rock: this Victory carved from the olive tree, symbol of Peace and Prosperity giving for eternity the most ephemeral fruit.

And this as well, this symbol, the olive tree carved by man's hands, this gesture of offering, certainty and light, this belongs to everyone.

Greek monasteries.

Greek monasteries. This word means in ancient Greek "fish". The symbol of the Ikhthus is commonly represented with two intersecting arcs, in order to make it look like a fish. This symbol was a secret symbol used by the first Christians. The letters of the word fish bear in fact another meaning. Ikhthus is in reality a word formed from the first letters of several words:

This word means in ancient Greek "fish". The symbol of the Ikhthus is commonly represented with two intersecting arcs, in order to make it look like a fish. This symbol was a secret symbol used by the first Christians. The letters of the word fish bear in fact another meaning. Ikhthus is in reality a word formed from the first letters of several words: